Peel Island is a green, treed island located in the southern part of Moreton Bay, Queensland, a mere 5 kilometres from suburban Cleveland and a similar distance from Dunwich on South Stradbroke Island. It is a favourite weekend playground for residents of Greater Brisbane with the expansive and sandy south-facing beach of Horseshoe Bay.

It is not unusual to see hundreds of various watercraft here on a sunny weekend, especially if there is a breeze from the north, as Horseshoe Bay offers protected, swimmable beaches and no alarming currents. The island is a national park managed jointly by Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service (QPWS) and the Quandamooka people. The island is now uninhabited, but it was not always so.

There are few obvious indications that Peel Island once housed Australia’s first and Queensland’s largest, purpose-built multi-racial lazaret, or leper colony. In part, this is because the lazaret was located on the north-west corner of Peel Island in a location that was, and remains, isolated. Out of sight, out of mind. The lazaret site is located within a section of Peel Island that is closed to the general public and because of this continued isolation, many of the structures of the former lazaret remain in various stages of decay.

Recently, we were fortunate to participate in a rare guided tour of these remains in the company of local author and historian, Peter Ludlow. A Flotilla of 14 yachts from the RQYS Cruising group left Manly Boat Harbour and braved 30-knot gusts from the south-east. This made for an uncomfortable anchorage with a lee shore in Horseshoe Bay and for a few hours it looked as though we might have to abandon plans of going ashore. Fortunately, the winds abated, and we manned our dinghies to be met on shore by Scott Fowles, president of the Friends of Peel Island Association (FOPIA). After a short safety briefing, we trekked 2.3km across the island to the site of the former lazaret.

Upon arrival, we were struck by three things — the silence, the isolation and mosquitoes. The lazaret at its peak was home to 500 people but now it is a ghost town, occupied only by mosquitoes, a few snakes and the occasional QPWS ranger and volunteers from FOPIA. Both QPWS and FOPIA have done a splendid job of restoring selected buildings but even these buildings exhibit some deterioration from the relentless surge of the elements. Nature wants to once again engulf this place and ultimately, without constant attention and funding, it will succeed.

Peter Ludlow explained to us that in the 1850s, Chinese miners who flocked to the goldfields brought with them the bacterial disease, leprosy, which then quickly transferred to the Aborigines and South Sea Islanders who had little natural immunity to the disease. Today, the disease is known as Hansen’s Disease.

Peter added that back then, the disease was believed to be highly contagious with no known cure. By the 1890s, sufficient Europeans had also contracted the disease to force the Queensland Government to pass the Leprosy Act of 1892. This made leprosy a notifiable disease and forced those who contracted the disease to be sent to designated lazarets, or leper colonies, for treatment isolated from the general community. Because there was no known cure at that time, for many, such internment was probably going to be a lifetime sentence.

We were treated to a guided tour of the former nurses’ quarters, day surgery, white female accommodation, white female bathhouse, recreation hall, ‘coloured’ men’s accommodation, white male accommodation and bath house. The highlight of the tour for me though was the now overgrown and derelict cemetery.

Over the 52 years that Peel Island was an operating lazaret, over 500 patients passed through its doors. Most went into remission and eventually left the island. In some instances, the disease reoccurred, which meant patients had to return to the island, sometimes even for a third or fourth time. However, 200 patients died on Peel Island. Owing to the policy of isolation, their bodies were never allowed to be reunited with their families and they were buried generally in a pauper’s grave within the cemetery. There are few headstones in this cemetery, with most graves marked only by a simple numbered cast iron cross. To think that this was the sum total of people’s lives is haunting indeed.

The lazaret was divided into compounds that separated white and non-white patients as well as segregation according to gender. There were dramatic disparities between the treatment of non-white patients (Aboriginals, Torres Strait Islanders, South Sea Islanders and Chinese) and white European patients. This was reflective of the social attitudes of the time.

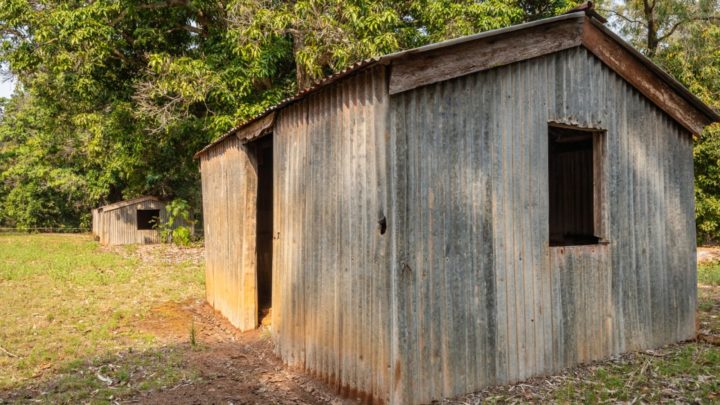

This disparity is still evident today in the standard of accommodation for the whites and the non-whites. While white patients had individual bungalows with a steel spring bed, chair and dresser, many non-white patients lived in tents until their huts were constructed. In the early years of the lazaret, the huts in the non-white compound were made of corrugated iron, with corrugated iron rooves and walls. Windows were made by cutting the wall with tin snips. At first, the floor was merely the existing dirt, which would turn to mud in the rain as there were cracks in the roofs. The floors were later covered in cement. Some of these huts remain. They appeared to us to be suitable only for livestock.

It was hard to comprehend what life must have been like for the leprosy sufferers. You could imagine that a few days or weeks here could be tolerable, but to be incarcerated here for years and possibly the rest of your life was just a mind-numbing thought. The boredom must have been unimaginable. Whilst staff could freely leave the island, patients were confined here, often for many years and without a release date, irrespective of race, gender or age.

A three-day furlough was possible, but if patients did not return, they would be hunted down by the police and forcibly returned to the island. This was certainly no holiday camp! To alleviate the monotony male patients would often go fishing or both men and women would create gardens and raise poultry to pass the days. The remnants of those gardens are evident today only in the form of bulb flowers that have breached the confines of the original gardens and are now prolific throughout the lazaret.

Peter Ludlow recounted how families would be literally torn apart when health authorities would forcibly remove suspected lepers from homes, workplaces and even schools and swiftly transport them to Peel Island. Cut off from all society, with their only crime being that they had contracted a disease, these people were treated unbelievably harshly.

This was not Nazi Germany, this was our recent Queensland past. It goes to show what lengths people, and governments will go to when ignorance and prejudice together with absolute power are allowed to prevail. It’s a lesson that we should all remember and endeavour to prevent in the future. It is easy to condemn historical acts, but then times were different — or were they? In some ways, the same fear and hysteria accompanied the onset of AIDS, so I wonder if we are really that enlightened these days after all? Ironically, after the island was decommissioned as a leper colony, it was discovered that the strain of leprosy which infected its inhabitants was non-contagious. How incredibly tragic!

In January 1947, Peel Island patients were treated with the first of several sulfone derivative drugs, which were developed in the United States. These drugs proved to be effective but often took up to six months to subdue the bacteria.

At the conclusion of the tour we ambled back to Horseshoe Bay the way that we came all a bit amazed by what we had witnessed. As we enjoyed a traditional yachties ‘sundowner’ on the beach, we reflected that we were indeed far more fortunate than prior generations.

In 1993, the cultural significance of Peel Island was recognised and it was consequently placed on the Queensland Heritage Register. In December 2007, Peel Island was declared as Teerk Roo Ra (place of many shells) National Park and Conservation Park. What will become of the lazaret? The future is definitely not certain, but one thing is clear — without constant funding and maintenance the bush will reclaim the site and perhaps, one day, only the flowers will remain as a final leprosy legacy.

If you get the opportunity, do visit Peel Island lazaret. Permission to access the site must first be obtained from Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service. If you would like to know more about Peel Island, then you might like to read Peter Ludlow’s numerous informative books and blogs. Alternately, if you are interested in becoming a volunteer I recommend you contact the Friends of Peel Island Association.