Reading Readit – A little book with a big punch

Coming to a book with no expectations, just prepared to take it as you find it, is the way I approach the choices of our library book club. With this attitude I’ve read novels I would never take from the shelves otherwise.

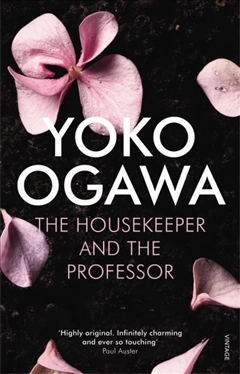

The latest (and one of the most awesome) is The Housekeeper and the Professor by Yoko Ozawa, translated from the Japanese by Stephen Snyder, who I cannot praise highly enough for his careful, respectful translation. I don’t know if Stephen captured the author’s intent, but he produced a beautiful story for this English-only reader.

In 1975 the Professor was in an accident and ever since he has had a memory span of 80 minutes. He knows this because there is a note attached to his suit which tells him so. Effectively, the world stood still in 1975; the Professor remembers very little of what happened before his accident but knows nothing of what happened since the accident.

In 1975 the Professor was in an accident and ever since he has had a memory span of 80 minutes. He knows this because there is a note attached to his suit which tells him so. Effectively, the world stood still in 1975; the Professor remembers very little of what happened before his accident but knows nothing of what happened since the accident.

There are lots of notes on the Professor’s suit and they mean something to him, even if they are incomprehensible to anyone else. The Professor lives in an unpretentious cottage at the rear of his sister-in-law’s home. He has a very bad reputation with the domestic agency who provides his housekeepers – 9 blue stars indicating staff doesn’t stay long in the little cottage.

The story is told through the voice of the Housekeeper – why am I not telling you her name? Simply because she is never given one – other than one character given a nickname, (explained later) there are no names attached to the major characters. Strangely, this was not a problem for me; the novel develops so organically, I did not notice there were no personal names until I was well into the novel and by then it did not matter.

When the sister-in-law employs Housekeeper number 10 and she arrives at the Professor’s cottage, the first question he asks is her shoe size, “no bow, no greeting. If there is one ironclad rule in my profession, it’s that you always give the employer what he wants: and so I told him. “Twenty-four centimeters”. “There’s a sturdy number,” he said. It’s the factorial of 4.” He folded his arms, closed his eyes, and was silent for a moment.”

Later the Professor asks for the Housekeeper’s birthdate which is February 20. That pleases him immensely as in numbers it is 220. The one thing the Professor has not forgotten is mathematics, in fact, he is a mathematical genius. His hours are spent in his study completing problems in mathematics journals, all of which take numerous pages of calculations to solve. When the Professor is happy with the neatness and correctness of his entry, he gives it to the Housekeeper to mail for him. The prize cheques which arrive because he has won are ignored – once the problem is solved it has no further meaning for him.

The Housekeeper is not an educated person and she has no conception of what the Professor is trying to explain to her with his numbers, but because of his inability to recall anything which happened over 80 minutes ago, she can keep asking him the same questions which he has no problem answering again. Numbers start to have a meaning to the Housekeeper beyond anything she imagined, and her self-esteem grows with her ability to see the patterns seen by the Professor.

Another note is added to the Professor’s suit coat when Housekeeper 10 arrives; it says simply housekeeper and has a circle which is his “picture” of her. A few weeks later he adds to this portrait the sign for square root, indicating her eight-year-old son. When the Professor learns the boy is home alone whilst his mother works, he becomes very irritated and insists that the boy should come to his home after school. On their first meeting, he nicknames the son Root, because his head is flat.

I absolutely loved this simple beautiful story about love, loyalty and the way human beings can be kind to each other without expecting anything in return. With limited number theory knowledge (read high school mathematics) I followed the numerical knowledge in its pages. Much of it I found utterly poetical, such as “For him, prime numbers were the base on which all other numbers relied: and children were the foundation of everything worthwhile in the adult world.”

Yoko Ogawa is such a lyrical writer; her understanding of how the Professor processes information in his flawed brain is sympathetic and kind so that the Housekeeper does not judge him, she accepts him. The boy Root exhibits that beautiful empathy you find in children. Yoko, obviously, has an amazing knowledge of the finer points of mathematics and can reproduce this knowledge so it is understood by someone like me.

The Housekeeper only worked for the Professor for 3 years, but their friendship and the dignity it brought to both of them, and to Root, lasted for the Professor’s lifetime and beyond – it affected them all in positive, affirming ways.

Only 180 pages long, The Housekeeper and the Professor, by Yoko Ogawa, is a little book with a big punch – and it’s available now from Dymocks:

Proudly Australian owned and operated

Proudly Australian owned and operated