It sure is breathtaking, but its fascination as a travel destination extends far beyond that. South Georgia Island is legendary for its tales of heroic leadership and message of environmental hope – stories that deserve telling, just as every lover of adventure travel deserves to hear them. Be warned, though; once heard they aren’t easily forgotten.

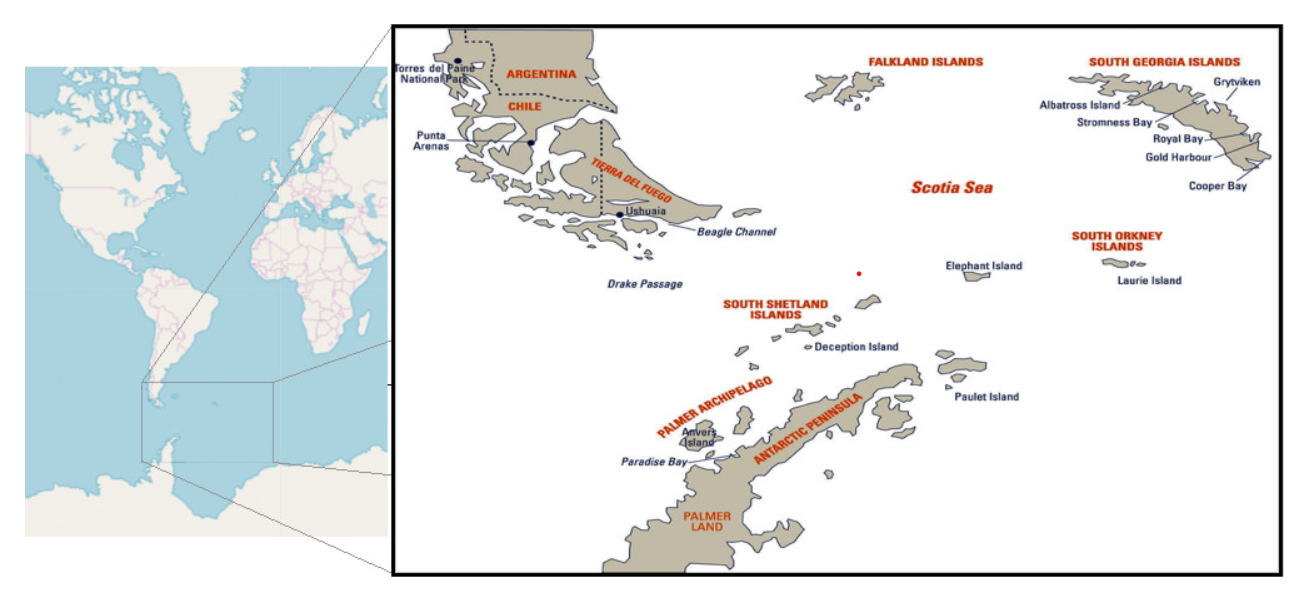

South Georgia Island has long been on my mind, both for its incredible stories and – here’s the breathtaking bit – its jaw-dropping landscapes, wildlife-packed beaches, whale-filled oceans and otherworldly icescapes. True, it is both small, at 3900 square kilometres, and remote at some 2000 kilometres from both the southern tip of Argentina and the Antarctic Peninsula. But, it will draw you, as it drew me.

Thankfully, I found the island easy to reach, although I was mighty choosy how I would experience it. A 20-day National Geographic – Lindblad cruise to Antarctica, South Georgia and the Falklands had the length, luxury and natural history focus I was after – including Peter Hillary among the accomplished naturalists, adventurers and scientists onboard to educate us. I could imagine no more appropriate way to visit an island fabled for leadership and environmental hope than with a company at the forefront of sustainable ocean travel.

Naturally, we would not be the first to go ashore on South Georgia. Explorers Anthony de la Roche and Captain James Cook led that charge, both claiming and naming it in their turn. However, its most famous landing would occur almost 150 years after Cook. For those unfamiliar with the story of polar explorer, iconic leader and tenacious holder of hope, Sir Ernest Shackleton, and his ill-fated 1912 – 1917 Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition and epic rescue, get ready for the travel adventure of all time.

With his ship, the Endurance, crushed by Antarctic pack ice, Shackleton would encourage and guide his 23 crew through a gruelling, 22-month ordeal that included five months camped on fracturing ice and a horrendous journey in uncovered lifeboats through frigid ocean to Elephant Island. Leaving 18 of his crew on the island, Shackleton and the other five men then embarked on a 16-day winter crossing of the tempestuous Scotia Sea in the hope of reaching aid at South Georgia Island.

When they finally landed on South Georgia’s southern side, the boat and three of his men could go no further. Stromness whaling station and sanctuary lay across ice-crusted mountains on the northern side, so with barely a pause and scant food, clothing and equipment, Shackleton and his two least exhausted men got walking.

Driven by desperation and determination they made it, and every one of Endurance’s crew would be rescued in coming months. However, Shackleton himself would die on a subsequent voyage south and be buried at Grytviken, another South Georgia whaling station and its largest settlement.

We walked Shackleton’s last kilometre into Stromness and paid tribute at his Grytviken gravesite on our cruise’s 5-day exploration of South Georgia, both stations now no more than eerie, rusting memorials to the less admirable side of the island’s human history. More than 175,000 whales and close to two million fur seals and elephant seals were slaughtered there in the twentieth century, the industries collapsing only when the animal populations did.

As if enough harm wasn’t done, the whalers and sealers delivered other agents of mass destruction – mice and Norwegian brown rats. These little critters and their burgeoning progeny would continue the task of annihilating South Georgia Island’s wildlife, taking invertebrates, birds, chicks and eggs by the million. Many petrel and prion species eventually abandoned the island altogether, and other endemic bird and insect species came perilously close to extinction.

Today, it is hard to imagine how South Georgia must have looked, sounded and even smelled back then. Envisaging the now pungent, penguin-packed, seal-strewn beaches of St Andrews Bay, Salisbury Plain and Gold Harbour without wall-to-wall feathers, fat, fur and fights, is beyond difficult. Just as picturing the skies without gracefully arcing birds or – even worse – as silent as the abandoned whaling stations, seems impossibly sad.

Gaping holes had been chewed in South Georgia’s fragile ecosystems, with the damage seemingly irreparable. Mercifully – especially for avid wildlife tourists like me – it wasn’t, with hope and help arriving in the form of now legendary, world-leading groups of conservationists.

That our cruise ship passengers could see hundreds of thousands of breeding, birthing and battling animals lining South Georgia’s bays is solely due to the herculean vision, effort and leadership of the South Georgia Heritage Trust. In 2011, the Trust embarked on a massive, four-phase habitat restoration project aimed at eradicating the rodents, and with support from the Friends of South Georgia Island (FOSGI), British Antarctic Survey (BAS) and pest eradication experts from New Zealand, were able to declare South Georgia officially rodent-free on 8 May, 2017.

The birds, seals and whales then got busy on their part of the deal, and within a matter of years had effected noticeable repopulation and repair of their colonies and numbers. Of course, many still have a way to go and South Georgia’s albatross populations continue their heartbreaking decline due to bycatch in the krill and fishing industries. However, there is hope there, too.

Assisted by FOSGI, the Trust has now embarked on a programme to raise awareness of the plight of South Georgia’s threatened albatrosses and another aimed at safeguarding seal and whale populations. South Georgia waters are now protected by a 1.24 million square-kilometre Marine Protected Area, and both groups are supporting BAS efforts to measure whale foraging and krill consumption around the island to better manage the krill fishery.

If it can be done on South Georgia, everywhere else has a chance, provided leadership is brave and hope is held. For that reason, it is my own hope that South Georgia will always be on our minds, just as my incredible journey there and the island’s breathtaking beauty, will always be on mine.

For more information on the South Georgia Habitat Recovery Programme and the activities of the South Georgia Heritage Trust, go to www.sght.org.

Sue Halliwell travelled to South Georgia island on a National Geographic – Lindblad cruise. For more information on National Geographic – Lindblad cruises, go to www.au.expeditions.com.