I can thank Anglo-Irish polar explorer, Sir Ernest Shackleton, for my own incredible adventure.

It was an odyssey taken last year to mark the 150th anniversary of his birth; although I confess to cheating a bit. While I would follow in his remarkable footsteps, I thank Neptune and Poseidon it wasn’t in his shoes. I would not have had the endurance.

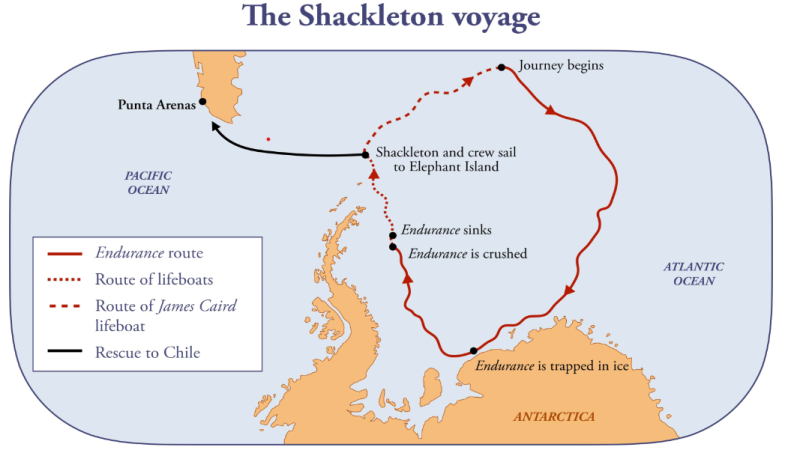

As admirers of Shackleton and the Heroic Age of polar exploration will know, Endurance was the prophetic name of Sir Ernest’s ship on his ill-fated British Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914-1917. It was this extraordinary voyage – and rescue – that I traced, and as I listened to its retelling in the plush lecture lounge aboard my National Geographic – Lindblad cruise ship, the National Geographic Explorer, I couldn’t help comparing our journeys.

While Shackleton and I had boarded our respective ships with the intention of reaching Antarctica via the Falkland and South Georgia Islands, we shared little else. I would be indulged and pampered on a 20-day luxury expedition cruise, whereas Shackleton and his crew … well, therein lies the tale.

He planned to be the first to cross Antarctica via the South Pole. However, before even reaching Antarctica proper he was stymied by pack ice in the Weddell Sea. Stuck fast, the Endurance drifted north for ten months before finally succumbing to the ice’s crushing force.

Anticipating this, Shackleton had already ordered his men to abandon ship, taking basic belongings, supplies, dogs and lifeboats. For the next five months they camped on a succession of ice floes, making a few unsuccessful attempts to reach land before the ice finally began to melt beneath them.

Shackleton then ordered the speedy loading of men and supplies into three lifeboats, and thus began a harrowing five-day journey north to precipitous Elephant Island in the South Shetland Islands, where they hoped to find solid ground, better shelter and enough to eat.

That all three lifeboats made it to Elephant Island is beyond belief. Rescue was still unlikely from here, though, so in the 6.7 metre lifeboat, the James Caird, ill-equipped but packing iron-will determination, Shackleton and five of his crew set off through the roiling, mid-winter Scotia Sea to human habitation at South Georgia Island.

That the six men survived this tortuous 1300-kilometre journey was a miracle, but the nightmare didn’t end on reaching the island’s southern shore. With the James Caird now unseaworthy and Stromness whaling station on the other side of South Georgia, Shackleton and his two least exhausted men embarked on a never-before-attempted crossing of its precipitous mountain range. “If you’re a leader, a fellow that other fellows look to, you’ve got to keep going,” he is famously quoted as saying.

In extraordinary testament to the power of human will, they stumbled, half-demented, into Stromness and sanctuary 36 hours later. I walked their last kilometre on arriving at Stromness aboard the Explorer, trying to imagine how that would have felt. I couldn’t.

Rest would be pitifully brief for Shackleton whose marooned and starving men on southern South Georgia and Elephant Island still required rescue. It would take another four frustrating months to complete the task, but he would do it, losing not one soul.

Tragically, Shackleton himself would die on his next trip to Antarctica in 1922, and just over 100 years later I found myself standing reverent at his grave at Grytviken on South Georgia Island.

Like me, many of our passengers had chosen this National Geographic – Lindblad voyage for its opportunity to shadow much of Shackleton’s Trans-Antarctic Expedition route – including paying our respects at his gravesite. Here we toasted ‘the Boss’ – Shackleton’s nickname – with a nip of whisky, and I offered my proudest salute.

From South Georgia we continued southwest across the Scotia Sea to the Antarctic Peninsula, the same passage taken by the James Caird, only in reverse. We saw our first whales and icebergs as the stabilizer-equipped Explorer sliced its way through sizeable seas, and again I wondered how six men in a leaky boat could have navigated this volatile stretch of ocean in the depths of winter. Where I could retreat indoors for an haute cuisine meal and a warm, serviced cabin, their solace consisted of a frozen canvas covering, basic rations and wet sleeping bags.

We approached Elephant Island at first, frigid light – looking forbidding and hostile to me but described by Shackleton in his journal as ‘paradise’. I watched from the deck as the Explorer nudged alongside Point Wild, the rocky slither of land on which Endurance’s crew lived under upturned lifeboats and on scavenged food while awaiting rescue. Nodding a respectful head in the direction of Shackleton’s centre-placed memorial, I fled indoors for a full English breakfast.

Our next few days comprised a delightful exploration of Antarctica – one of the most beautiful places on earth – and getting acquainted with its wildlife, including possible descendents of the orca pod that had tormented Shackleton’s men on their lifeboat trip to Elephant Island.

As we navigated the ice floes, I felt immensely grateful for the modern technology and onboard experts that would keep us safe here, knowing Shackleton’s men had the benefit of neither.

After four incredible days in Antarctica, the Explorer pointed her nose north toward the Argentinian port of Ushuaia, and again the message was sheeted home. While our two-day, southern ocean crossing would consist of sound sleep, great food, inspiring lectures and wildlife watching, Shackleton’s had held little sleep, merciless cold and terrifying winter swells. “Deep seemed the valleys when we lay between the reeling seas,” he wrote in his book, South! The Story of Shackleton’s Last Expedition 1914-1917, and I doubt it was an exaggeration.

Our voyages were poles apart, and I wondered how I could justify my supremely comfortable experience of it in the face of Shackleton’s hardship. Almost a century and a half was the answer: how far Antarctic and sub-Antarctic exploration has come in one hundred-plus years while still retaining the Heroic Age thrill.

Happy 150th birthday, Sir Ernest, and thanks for everything.

Sue Halliwell took the Antarctica, South Georgia and the Falklands voyage with National Geographic – Lindblad. To learn more about all National Geographic – Lindblad voyages to Antarctica, go to: https://au.expeditions.com/destinations/antarctica.