Perhaps you decided to investigate your ancestry and discovered many fascinating tales in your history. Perhaps also, you’ve been alone in the search and wanted to share your stories with relatives who might not be as interested as you are. This was the dilemma that plagued me after going down the ancestry rabbit hole.

I wanted to write about my discoveries in a way that was engaging, memorable and impressive. I wanted my family to be interested in the far away relations that we had. There were discoveries like Aunty May marrying Uncle George three months before cousin Bert was born, but this didn’t exactly make for page-turning reading: “May and George married at the Tavistock Registry Office in August 1939 just three months before their first child Albert was born.”

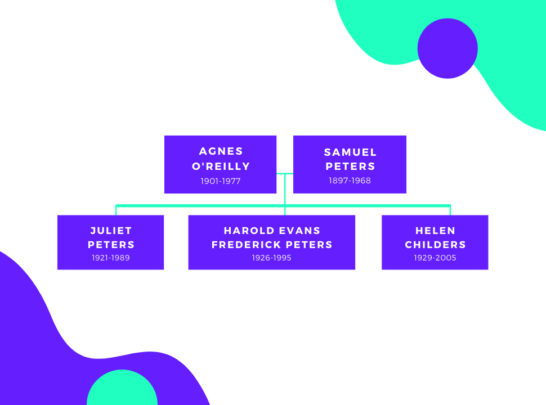

First, I collected all the facts I possibly could and drew up a timeline. For example:

I recommend including the locations, too. Then that information and other things I discovered about the characters allowed me to develop story lines about them.

I found out more about the context of these people. Where they lived and when? What was going on around them in the larger picture? For example, the dates above show that the younger generation were growing up at the beginning of the World War II. How did they react to that? What were the rationing restrictions?

I looked at the census papers; went to the addresses of my ancestors; and took photos of the homes or streets or new builds — whatever was there. I visited my city library to see if I could find pictures of the areas my family lived in. Then I imagined myself living there. Where was the toilet? Was it shared with other families? How many bedrooms were there for the family and how many people were there in that family? How large was the land they grew up on and what did that imply about their class? All these details brought life from the past alive.

Something I considered, and would recommend you do too, is consider the stories already known about the generations that have just preceded me. Everyone knows one or two stories about the past. Why are these tales remembered? What is their significance?

For instance, when I went to have one of my back molars extracted, I remembered that my mother had all her teeth removed when she was 30. I was in so much pain and it reminded me that my mother did it voluntarily — simply because she disliked her smile. What could I draw from this? Was my mother vain? Or was it related to another story from her past where her mother criticised her for congratulating herself on winning the May Queen’s crown. Tell those stories before they’re forgotten.

There are church records and churchyards too! My father visited every parish council in the areas where his ancestors lived and discovered christenings and graveyards in the books and under the ground of the surrounding churches.

Finally, I researched as much as I could about the laws and habits of the times. For instance, when my father was telling the tale of his relations in mid-Wales during the 18th century, he discovered his relative owned a large coaching house at St Asaph. This meant big business, as my father discovered when he researched how many coaching houses there were en route from London. Then he found out that the inheritance laws in Wales were different from those in England: in England the rule of primogeniture was enforced where the first born inherited everything. In Wales properties were divided and within a few generations assets had deteriorated to nothing. When my father discovered this relative had followed the English way, he imagined the arguments that must have followed between the second son and the father.

As in all ‘documentary’ writing, it was important for me to stick to the facts, but reimagine these facts as living, breathing exchanges. How would people have reacted to the essentials of the truth? If you’re unsure, present both sides of reality and make your history come alive.