When President Trump announced that he takes aspirin every day because he likes his blood “beautiful and thin”, it struck a familiar chord – not because of the phrasing, but because so many of us grew up believing that was exactly what you were supposed to do.

My mother certainly did.

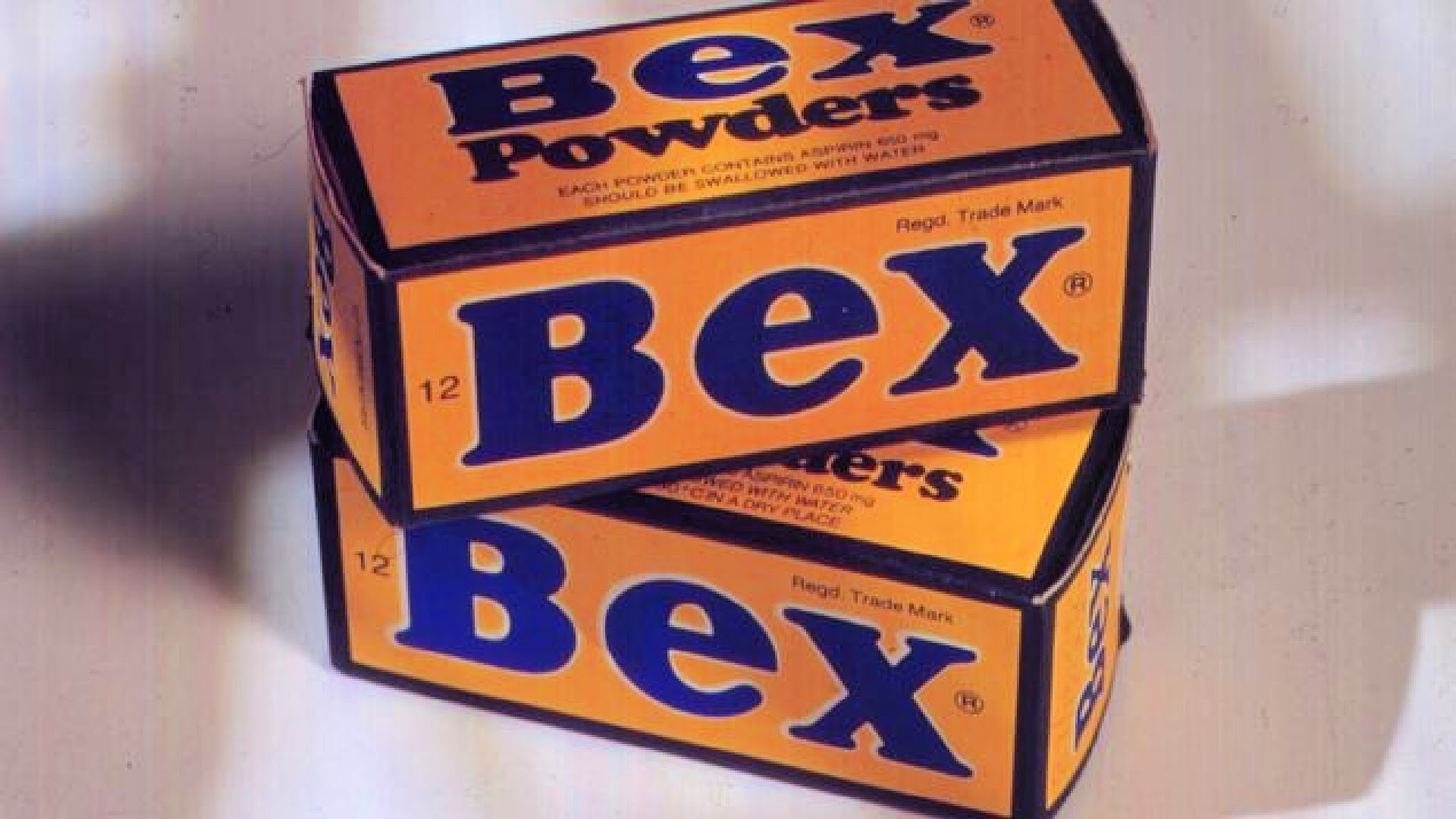

She took a Bex almost every day. Sometimes two. Headache? Bex. Tired? Bex. A bit off-colour? Bex. It sat in the cupboard alongside the tea and the sugar, less a medicine than a household staple. Mum lived to 80, which she would have taken as proof that it did her no harm at all.

And that’s the problem modern medicine has when it tries to tell older people that something they’ve done for decades is suddenly “not recommended”.

Aspirin is a good example. For years it was promoted as a near-miracle drug — easing pain, reducing inflammation, protecting the heart. Many doctors routinely advised older adults to take a low dose every day to prevent heart attacks and strokes. It became so normal that questioning it felt unnecessary.

These days, medical advice has shifted. Doctors now warn that daily aspirin can increase the risk of internal bleeding, particularly in older people, and that for many, the risks may outweigh the benefits unless there’s a clear medical reason. It’s not that aspirin suddenly became dangerous — it’s that research improved, long-term data accumulated, and nuance arrived.

But nuance doesn’t always land well with people who have been doing something “wrong” for 40 years and are still standing.

And aspirin isn’t the only thing.

Think back to the 60s and 70s. We smoked because it relaxed us. Doctors smoked too – right there in the consulting room. Sunburn was a badge of honour. Seatbelts were optional. Children rode in the back of utes. Antibiotics were handed out like lollies, and if you were tired, nervous or a bit flat, there was almost always a pill for that.

We trusted authority, but we also trusted experience. If something seemed to work, we stuck with it.

That’s why many older people remain sceptical of new medical advice. It changes. Frequently. One year eggs are bad; the next year they’re fine. Coffee is dangerous until it’s suddenly protective. Butter is replaced with margarine, then margarine quietly slips out of favour again. If you’ve lived long enough, you’ve seen the pendulum swing back and forth more times than you can count.

So when someone says, “We now know better,” the unspoken response is often: Do you? And for how long this time?

There’s also a deeper reason for the scepticism: personal history. Many people can point to parents or grandparents who ignored advice, lived hard, and still reached old age. These anecdotes aren’t scientific, but they’re powerful. They form a quiet counter-argument to every new guideline.

“My mum did it and lived to 80” may not hold up in a medical journal, but it holds up around the kitchen table.

None of this means modern medicine is wrong. In many cases, it’s undeniably better. We live longer. We survive things that once killed us. We understand disease in ways that were unimaginable 50 years ago.

But older generations don’t reject new advice because they’re ignorant. They reject it because they’ve been around long enough to know that certainty has a short shelf life.

There’s also fatigue. Being told, year after year, that something ordinary and familiar is actually dangerous becomes exhausting. Especially when the alternative is often vigilance, monitoring, and worry – all of which take a toll of their own.

Perhaps the answer isn’t to mock “beautiful thin blood” or dismiss the habits of the past, but to understand them. To recognise that trust in medicine is built not just on studies, but on relationships, respect, and an acknowledgement that people make sense of health through lived experience as much as data.

After all, if you’ve survived Bex powders, second-hand smoke, sunburn, and no seatbelts – being told to stop your daily aspirin might feel like one change too many.