Tea, Titles & Tiaras with Emily Darlow

Every royal family has a year they would dearly love to erase from the official record. For Elizabeth II, that year was 1992, the moment when decades of discipline, discretion and image management finally buckled under the weight of modern scrutiny.

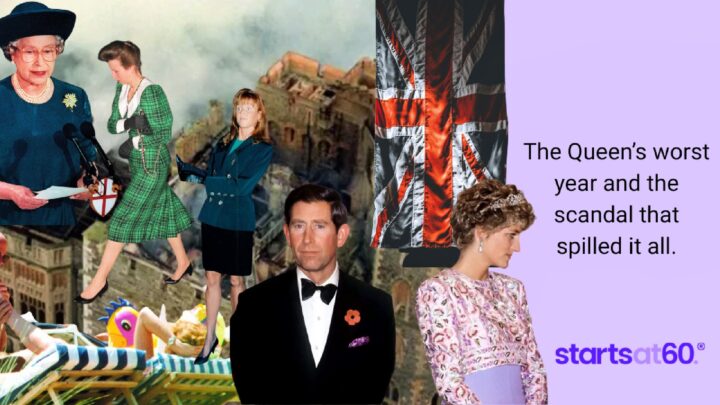

It was the year the Queen herself memorably described as her annus horribilis, a rare and carefully chosen admission from a monarch who had built her reign on emotional restraint. In twelve relentless months, royal marriages collapsed, secrets spilled into print, photographs did more damage than words ever could, and the Palace learned a lesson it had resisted for generations. The age old phrase of ‘never complain, never explain’ no longer protected the Crown.

By the end of 1992, the monarchy was bruised, unpopular and exposed in ways it had never been before. The fairy tale was officially over, and the public knew far more than the institution ever intended to share.

The year began badly and escalated quickly. The separation of Princess Anne from Mark Phillips was confirmed with little ceremony, barely registering as scandal by the standards of what was to come. Soon after, Buckingham Palace acknowledged that Prince Andrew and Sarah Ferguson were living apart, a polite phrase that masked a relationship already beyond repair.

At first, the Palace attempted to treat these announcements as unfortunate but manageable. Divorce was still uncomfortable territory, but Anne’s marriage had long been seen as unconventional, and Andrew and Sarah’s union was already widely viewed as unstable. What no one anticipated was how rapidly personal separation would become public spectacle.

Sarah Ferguson had never fit easily into the royal mould. She was warm, outspoken, tactile and emotionally expressive in a family that valued reserve above all else. Her early popularity faded quickly as the press turned on her weight, her spending and her refusal to behave like a quietly decorative duchess.

In August 1992, images of Sarah on holiday in the south of France exploded across newspapers. Sunbathing topless. Laughing. Her toes being kissed by an American financier. The pictures were humiliating, undeniable and impossible to contain. Any remaining goodwill evaporated overnight.

The Palace response was swift and telling. Fergie was effectively cut loose. Support disappeared while invitations dried up, and she became an object lesson in what happened when a royal woman embarrassed the institution publicly. The message was not subtle. She was outcast and pushed firmly to the margins, expected to retreat quietly from public life and take her humiliation with dignity.

Instead, Fergie spent the years that followed attempting to claw her way back into relevance, often with disastrous results. From ill-judged business ventures and awkward media appearances to public financial struggles that played out in full view, each attempt at reinvention seemed only to invite fresh ridicule. Time and again, just as sympathy threatened to return, another misstep would land her back on the front pages for all the wrong reasons.

She never regained her standing within the royal fold, and her long, uncomfortable exile marked a turning point in how the monarchy dealt with perceived liabilities. Fergie became the cautionary example. Redemption was not guaranteed, and once protection was withdrawn, there was no easy way back in.

If Fergie’s scandal embarrassed the Palace, Diana, Princess of Wales threatened to dismantle it.

The publication of Andrew Morton’s biography in 1992 confirmed the rumours that had circulated for years. Diana and Charles III were deeply unhappy, their marriage hollowed out by infidelity, emotional distance and despair. While the public had long suspected another woman, the book made clear that Camilla Parker Bowles remained a central presence in Charles’s life, an enduring relationship the Palace had tried and failed to suppress.

What truly shocked the establishment was not the revelations themselves, but the confirmation that Diana had secretly cooperated with the author. For the first time in modern royal history, a senior royal bypassed Palace channels entirely and spoke directly to the public, shattering the unspoken contract that royal grievances stayed private. Once that barrier fell, there was no way back.

Public sympathy swung overwhelmingly in Diana’s favour. Charles appeared cold and emotionally unavailable, Camilla was cast as the villain of the piece, and the institution itself looked archaic and unfeeling. The Queen, usually master of events, found herself reacting rather than directing, struggling to contain a narrative that was now being written beyond Palace walls.

As if scandal fatigue had not yet peaked, November delivered a moment so symbolic it felt almost scripted. Windsor Castle caught fire in the early hours of the morning, the blaze spreading rapidly through the historic building and burning for more than 15 hours, destroying or damaging over a hundred rooms, including priceless state apartments.

As flames tore through the roof, images emerged of members of the royal household scrambling to rescue artworks, furniture and irreplaceable treasures. The Queen and Prince Philip were both on site, calm but visibly shaken, overseeing efforts to salvage what they could, while staff and firefighters worked through smoke and debris to save pieces of history. There were even reports of her sons assisting where possible, a rare glimpse of the royal family in crisis mode rather than ceremonial composure.

The timing could not have been worse. Britain was in the grip of economic hardship, public patience with royal privilege was thin, and questions about who would pay for the restoration ignited fury. Many could not understand why taxpayers might be asked to fund the repair of a palace while ordinary households were struggling to stay afloat.

The image was irresistible and unforgiving. A monarchy engulfed in flames, both physically and reputationally, its treasures carried out hurriedly as decades of carefully cultivated mystique burned alongside them.

It was against this backdrop that the Queen delivered her speech marking the 40th anniversary of her accession, referring to the past year as her annus horribilis.

It was understated, restrained and devastatingly honest. For the first time, she publicly acknowledged that her family’s troubles had damaged not just their reputation, but the institution itself.

What made 1992 so destructive was not simply the volume of scandal, but the loss of narrative control. For decades, the monarchy had relied on a compliant press, rigid protocol and emotional distance to manage its image. That world no longer existed.

Diana spoke openly, Fergie leaked directly to the press, Photographs replaced discretion and so began the UK tabloids driving the agenda stronger than ever before. Television brought royal dysfunction into living rooms night after night and the families silence, once a shield, now looked like guilt.

The Queen, who had perfected restraint, suddenly found herself presiding over a family that could not stop talking, leaking or being photographed at exactly the wrong moment.

The annus horribilis forced changes the monarchy had resisted for decades. Buckingham Palace was opened to the public in a bid to help fund the costly repairs to Windsor Castle and to ease growing public anger about royal privilege. In a significant symbolic shift, the Queen also agreed to pay income tax voluntarily, acknowledging that the old rules no longer matched public expectations. Royal communications were modernised, the carefully cultivated wall of silence began to crumble, and divorce, once treated as a constitutional disaster, became survivable rather than catastrophic. But the deeper consequences are still playing out.

The Palace learned that royal marriages could no longer be sold as moral ideals, that women who married in could become existential threats rather than assets. And painfully, that emotional neglect bred public rebellion.

You can trace a direct line from 1992 to the slow, deliberate rehabilitation of Charles and Camilla, a process managed with extreme caution and an almost obsessive attention to public sentiment. It is there, too, in the protective cocoon built around William, Prince of Wales, whose marriage and family life have been guarded fiercely from the kind of scrutiny that consumed his parents. And it is impossible to ignore the echo of that year in the catastrophic breakdown between Harry, Duke of Sussex and Meghan and the institution itself, where old instincts for control, silence and containment resurfaced with damaging force. The lessons of Diana and Fergie were learned in parts, but applied unevenly, leaving the monarchy better prepared for some crises and fatally exposed to others.

As a final chapter in our scandal series, the Queen’s annus horribilis feels like the perfect full stop. Not one rogue affair or a single rebellious royal, but a systemic failure played out in public, forcing reform through humiliation rather than choice.

This series was never just about recent headlines or the scandal of the moment. Long before Wallis, Andrew, Diana, Fergie and Meghan the monarchy has been shaped by the same recurring tensions between duty and desire, secrecy and exposure, survival and sacrifice. Each generation dresses the problem differently, but the pattern remains remarkably consistent.

1992 was simply the moment the façade cracked wide enough for everyone to see it. The year when centuries of carefully managed privilege collided with a modern world that no longer accepted silence as an answer. The Crown survived, as it always does, but only by changing just enough to endure.

The tea has been spilled, the tiaras have slipped, and the scandals have come and gone, but the institution endures, not because it is flawless, but because it adapts when it has no other choice. And that, perhaps, is the most revealing royal scandal of all.

Next week we will return with the latest from the royals and what they have been doing over the break until then, and with considerably calmer headlines, keep the kettle warm.