Carol Spencer has seen Sydney at its best and worst.

In 1960, homosexuality in NSW was illegal and would be for another 24 years. While cross-dressing was not against the law per se, police routinely deemed it “offensive behaviour”, which was illegal. Spencer, better known as Carlotta, was arrested under that charge while walking home from her job in Kings Cross. At the time, she was still legally a man. The wheels of process followed and she faced court.

“I said to the judge, ‘What’s the charge?’ He said, ‘You’re dressed as a woman’, which was called offensive behaviour,” she recalled.

“And I said, ‘You’ve got a wig and a robe on. What’s the difference?’ He laughed his head off and dismissed the case.”

How times have changed.

“I was a bit of a smart ass,” Spencer told Starts at 60.

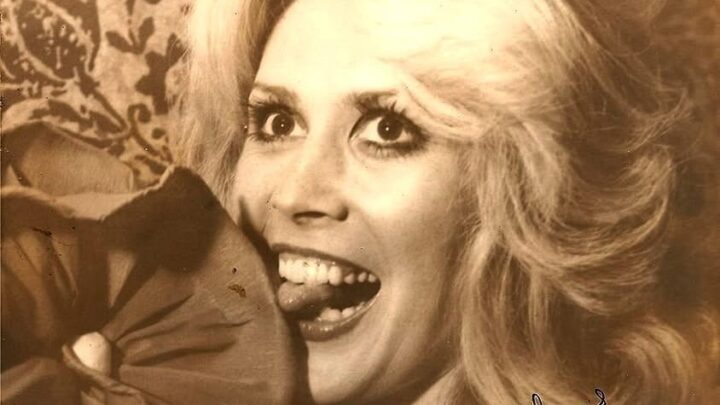

Describing Carlotta as a trailblazer for transgender rights — essentially the right to exist without persecution, ridicule or isolation — is a designation well earned. It is one she has embodied through a six-decade career as a public figure and performer.

That remarkable career began with a fairly unremarkable childhood for the person then known as Richard Byron, who left home at the age of 15, fleeing an abusive stepfather. After training as a hairdresser and makeup artist, Byron’s life changed when she crossed paths with legendary event promoter Lee Gordon at a party.

At the time, Gordon was famous for promoting concerts with major stars such as Frank Sinatra, Shirley Bassey and homegrown talent Johnny O’Keefe. His encounter with Byron, by then performing cabaret in drag, sparked the idea for what would become Australia’s first drag club in Kings Cross. It began as the Rheinschloss, became The Jewel Box, and ultimately headlined the iconic male revue Les Girls.

“He saw me at a party and he said ‘God, I’ve got an idea for a show’.

“And that’s when we opened up in a beer house called the Rheinschloss.”

Alongside Gordon at the helm of the Rheinschloss was notorious Sydney crime figure, Abe Saffron.

“We were a different breed of entertainer, see. We were all having sex changes and things, you know. It was a different period. You’ll never see the likes of us again like in those days.

“People would come to Les Girls and they’d say, ‘Oh they’re not bloody blokes, I can’t believe it.’”

It was Lee Gordon who coined the name Carlotta.

In the 1950s and 1960s, living and working in Kings Cross meant inhabiting a world that never quite slept – and never entirely behaved. By day it could look almost respectable. Boarding houses airing their sheets from iron balconies, café owners hosing down pavements, and shopkeepers greeting regulars by name.

But even in daylight there was an edge to the place, a sense that the night had merely stepped into the back room for a smoke. Soldiers and sailors on leave lingered over coffee, artists sketched in notebooks, and gossip travelled faster than the buses up Darlinghurst Road.

When the sun went down however, Kings Cross transformed. Neon signs flickered into life, jazz could be heard from basement clubs, and the streets filled with a vivid mix of locals, performers, hustlers, sex workers and off-duty police. Work in the Cross was often nocturnal and improvised, with people bartending until dawn, singing for tips, dancing in smoky rooms, or writing copy at impossible hours for tabloids that thrived on scandal. Many scraped by on cash-in-hand wages, living from one payday to the next, but there was also a sense of freedom that manifested itself in so many ways in post-war Australia.

For women, queer communities, migrants and the creative types, Kings Cross offered anonymity and tolerance. It was a place where unconventional lives could be lived more openly, even if discretion was still essential.

“The prostitutes on the corner were glamorous. They were in Chanel suits and there were no drugs around,” Carlotta remembers.

“Well, if there were, you didn’t see them.”

Amid the underbelly of the Cross, police corruption and organised crime were facts of life rather than headlines, and residents learned the unspoken rules quickly – who to avoid, who to pay, and when to keep your mouth shut. Yet amid the danger and the grind, there was camaraderie. People looked out for each other because no one else would.

For those who lived and worked there, it was exhausting, exhilarating and often precarious. It was a place that could chew you up or set you free, sometimes in the same night.

By Carlotta’s reckoning, the Cross truly turned seedy in the 1970s, driven largely by the arrival of “the R&R” – US service personnel returning from Vietnam.

“They brought the drugs and they used to hang out at the Bourbon and Beefsteak a lot, and then the prostitutes started getting on drugs and it just took over. You’d see people lying in doorways with drugs and needles hanging out of their arms.

“You speak no evil, see no evil, hear no evil, and that’s probably why I never ended up with some cement shoes,” Carlotta mused.

“But I was very well looked after by Abe Saffron. He protected me because we had Nazi police around, and of course the reason they protected me was because I was a money draw.”

With Les Girls firmly established as a Cross institution, Carlotta’s career took another turn when one night’s audience included a producer from the groundbreaking television series Number 96.

The show, already generating controversy for fearlessly introducing taboo themes such as homosexuality, abortion, rape, interracial romance, drug use and more, approached Carlotta about playing Robyn Ross. The character broke all conventions for a scripted show, with Carlotta becoming the first transgender actor to play a transgender character.

Carlotta credits fellow cast member Pat McDonald, who played Dorrie Evans, with mentoring her during her six-month stint on the show.

“It was the most popular TV show on Australian television. I mean, kids used to wag school to come home to watch it.”

She believes the show has aged well and was revolutionary for its time, though she laughs now, describing Number 96 as “like a Doris Day movie” by today’s television standards.

The experience gave Carlotta a lasting taste for television. In later years, she became widely known as a regular panellist for nine years on Network Ten and Foxtel’s Beauty and the Beast, frequently sparring with host Stan Zemanek.

“It was a great period. It was when you could say things, political correctness wasn’t about, you could say what you like. I always say political correctness ruined a lot of everything.

“The late Brian Walsh, who was the Executive Director of Television at Foxtel, came and saw me in a pub one night and said ‘I’d like to put you on Beauty and the Beast’

“I thought, oh, I don’t know if I could do that, and then I went in and I clicked with Stan, and that was history after that.”

Much like her everyday life, controversy followed Carlotta during her run on Beauty and the Beast. The show covered plenty of highly personal, controversial issues, both highly public and more intimate and personal. Carlotta describes it as “a very happy period in my life”.

Not everybody saw eye-to-eye, with high-profile names such as Lisa Wilkinson tossed out as being frequently combative, while Carlotta said others such as Jeanne Little often backed her views.

“We did a segment about Muslims one day, and I’d already read the Koran in English, and she happened to make a catty remark saying ‘Oh, have you been reading’ and Jeannie popped up and said, ‘Ah Carlotta’s got a brain love, she’s not just a showgirl.”

That intellect has long placed Carlotta at the forefront of gay and transgender rights, even when she didn’t set out to be an activist.

“I tried to help, you know,” Carlotta remembered.

“Don’t forget, it was hard for a lot of gays in those days, but once Oxford Street opened, they did their own race and all that. They’ve always been appreciative of what I did in the old days because, we got bashed by police and all that business.”

Whether quietly living her life or loudly demanding acceptance, Carlotta says she has no regrets.

“You either like me or you don’t, because we’re here too short a time, so if people don’t accept me, they don’t. I don’t dwell on that.

A new book released this week by former Les Girls compere Stan Munro and titled ‘Secrets of a Showbiz Dame’, recounts many stories from that era. Among them, Munro writes that had Carlotta taken her talent overseas and showcased her singing ability, she would have become as big as Barry Humphries and his eponymous alter-ego, Dame Edna.

Carlotta didn’t just survive an era that tried to erase her – she helped rewrite it. With wit as sharp as her eyeliner and courage stitched into every costume, she turned visibility into power and performance into protest. Her legacy endures in the freedoms others now take for granted: proof that sometimes the bravest revolution begins in a frock, under hot lights and daring the world to look.