By Heidi Douglass

Centre for Healthy Brain Ageing (CHeBA), UNSW Sydney

Sydney local Brian Barry turns 102 today. He doesn’t think of himself as remarkable. He’ll tell you he “just kept going”, that his long life is “luck”, and that he talks “a lot of rot”. But sit with him for even a few minutes and a very different picture emerges: a sharp mind, quick humour, deep empathy – and a philosophy of life that quietly mirrors what decades of brain ageing research has been trying to explore.

Ageing, Brian would say, comes for all of us. Dementia doesn’t have to.

This distinction has never been more important. As of 2025, dementia is the leading cause of death in Australia, surpassing heart disease and cancer. More than 400,000 Australians are currently living with dementia, and that number is expected to rise steeply as the population ages. Yet despite how common it is, dementia is still widely misunderstood – often assumed to be a normal or inevitable part of getting older. Research tells us that this simply isn’t true.

When asked what he says to himself each morning, Brian doesn’t hesitate: “You wake up every morning, I say to myself: Brian, you’re here another day. Thank the Lord.”

It’s a simple ritual of gratitude. For CHeBA’s researchers, it’s also the mindset of a “super-ager” – someone in their 90s and beyond who maintains unusually good memory and thinking abilities for their age.

Brian’s conversation flows effortlessly across a century of history: the Great Depression, World War II in New Guinea, the evolution of Sydney’s suburbs, raising children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren, and caring for his beloved wife Rose through dementia. His recall is detailed, his reflections nuanced, his humour intact.

“I never thought I’d live to 100,” he says. “When you’re a little boy, it never enters your mind.”

And yet here he is at 102, engaged, thoughtful, and very much mentally present.

From bread and dripping to Macca’s: A childhood of simplicity and resilience

Brian grew up in Cremorne Junction, behind the old Orpheum picture theatre. His childhood was marked by poverty, creativity and community.

During the Depression, food was simple and nothing was wasted.

“Bread and dripping was a big thing,” he recalls. “You thought it was the greatest thing.”

Christmas meant one precious chicken for the whole family. His father would bring it home and they would use nearly every part of the chicken for food.

“At Christmas time, you got a pair of shoes, but you couldn’t wear them to school – they were just for visiting Uncle Bob and Auntie May. You went to school with bare feet, even in winter. It never entered your mind that you had to have shoes on.”

Life was hard, but it was shared. Neighbours swapped eggs for vegetables. People knew each other’s names. Children were taught respect.

“Manners were taught at home, not out in the street,” Brian says. “You opened the door for your mother. You gave up your seat on the bus. If I didn’t, I’d get my ear pinched.”

That strong community fabric – connection, respect, reciprocity – is now recognised as one of the most powerful protective factors against dementia. Brian never heard the term “social connection” as a boy. He just lived it.

A life of movement, service and people

Brian left school at 15. His first “dream job”? A sweet factory in Rozelle, making lollies.

“I thought I’d struck gold,” he laughs. “A lolly factory!”

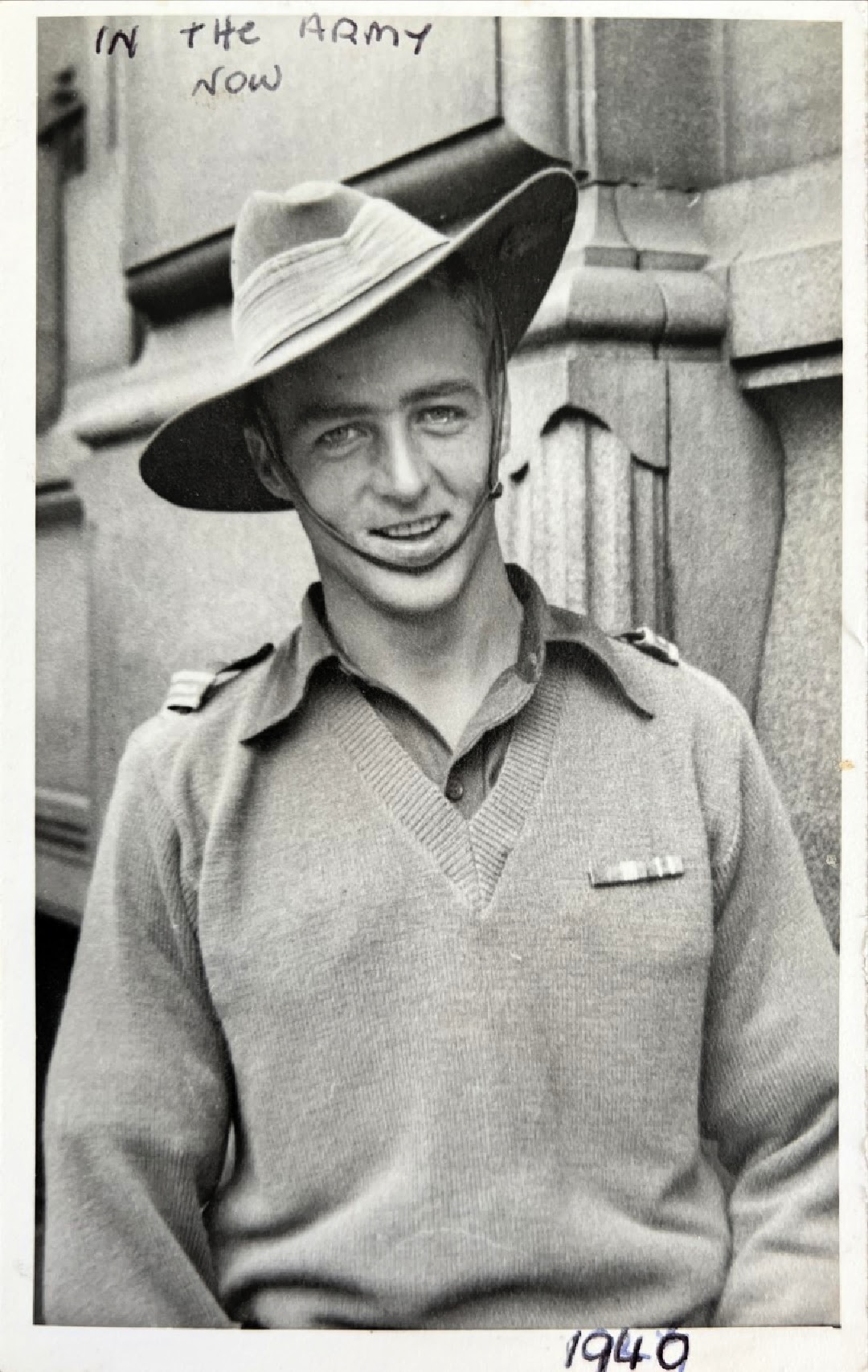

When the war came, the factory switched from sweets to bandages, and Brian was called up. He left Sydney for the first time in his life – not just across the harbour, but all the way to New Guinea, where he served two and a half years.

“You see the war and you see these poor blokes being brought out on stretchers, only young in their life,” he says quietly. “Some would never walk again. Bloody awful.”

After the war he worked as a tram conductor, then tram driver, then bus driver – on his feet, interacting with people all day. Later, he spent 20 years as a National Rugby League referee, rising to first grade and grand finals.

“I enjoyed every minute of it,” he says. “The camaraderie with the other referees – you never forget it.”

Legendary rugby league referee Bill Harrigan OAM says that throughout his career with the National Rugby League, Brian earned himself a reputation for fairness, professionalism and a dedication to the sport.

“Brian is one of the world’s greatest people – 100% a gentleman and I’ve only met a few of them in my lifetime.

“My only regret is that I didn’t know him earlier,” says Harrigan.

Even now, at 102, Brian continues to inspire. He only gave up driving a few years ago and still takes responsibility for the complete organisation of the referees’ annual lawn bowls days – a testament to his energy, engagement and commitment to community.

What Brian doesn’t emphasise – but his granddaughter Louise does – is that he never drank alcohol, never smoked and did loads of exercise throughout his life. He has always had a busier social life “than anyone I know”, she says. People are drawn to him because he is “loving and empathetic and very non-judgemental… always about others, never himself.”

From a research perspective, Brian’s lifestyle reads like a checklist of brain-protective factors: physical activity, social engagement, avoiding smoking and heavy alcohol, a strong sense of purpose and service to others. He doesn’t frame these as ‘health behaviours’. To him, they were just how you live a decent life.

Rose: Love, dementia and the power of kindness

If Brian is a super-ager, he is also something else: a man who has walked beside dementia and refused to turn away.

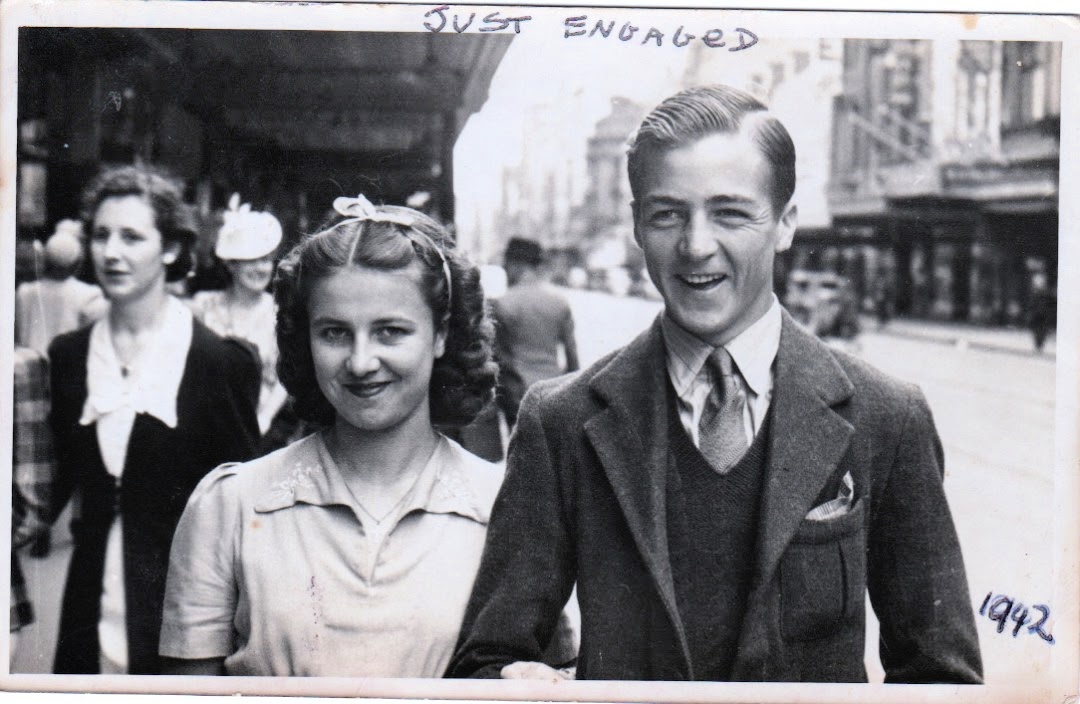

He met Rose when they were both 15, sitting on a gas box after a picnic at Clifton Gardens. She was “a good sort”, he remembers with a grin. Their first date was to see Gone with the Wind in the city; he nervously followed his mother’s advice to offer her an ice cream at interval. She said no.

So he ran outside, bought a box of scorched almonds, and brought them back.

They married, raised their children, paid off a house, and built a life defined by partnership. Rose managed the money, ran the home, and – in Brian’s words – “pulled me together.”

Decades later, in her early 80s, something started to change.

“She made an apple pie and put raw chicken in it,” he recalls. “Little things. Putting butter on the stove and setting it on fire. Leaving the bath running and flooding the house.”

At first he was frustrated. He didn’t yet have the language of ‘dementia’ – only a growing sense that there was something missing.

Eventually Rose was diagnosed and moved through hospital, rehabilitation and finally residential aged care. Brian visited every single day, often from 10am to 5pm. Some days she was warm. Some days she accused him of not visiting for weeks or of having someone else.

“It was very hurtful sometimes,” he says. “But I knew her brain wasn’t like mine anymore.”

Brian’s experience is shared by millions. In Australia, an estimated 1.7 million people are involved in the care of someone living with dementia – as partners, adult children, friends or neighbours.

Dementia is not just a diagnosis for one person; it reshapes entire families and communities, often over many years.

His advice to families now is simple and profound: “Be kind. Be kind to that person because their brain is not like your brain. They’re in their own body, but they can’t give you what they used to give you before.”

One of his most powerful memories is from Rose’s final days, when their grandson flew home from South Africa. Doctors thought she would not survive the day.

“He dropped his bag at the door and said, ‘I’m here, Nan.’ She smiled. He kissed her.

Rose died at 93, after about 13 years of cognitive decline. Brian describes the aftermath as “like walking into a wall”.

Still, he is unwavering about one thing: dementia research must keep going.

“If we can improve that little bit of knowledge and say to the person looking after someone with dementia that there can be hope in the later years, that would mean a lot.

If you keep working on it, you’re going to bring gratitude to a lot of people. Science today is brilliant.”

His message to CHeBA’s researchers is clear: “Keep trying.”

Ageing is inevitable. Dementia is not.

At CHeBA, our research – including 15-year long studies on centenarians, twins and people over the age of 65 – show that while ageing is universal, dementia risk is not fixed. Genetics play a role, but so do environment, lifestyle and social factors.

We now know that up to around half of the risk for dementia is explained by modifiable factors across the life course – including education, physical activity, blood pressure, diet quality, smoking, social isolation, depression and exposure to air pollution. Many of these factors are shaped long before old age, which is why brain health is a lifelong issue – and why prevention-focused research matters.

Brian’s story brings that evidence to life:

He avoided smoking and alcohol without ever thinking of it as a “health choice”;

He stayed physically active through manual work and years of refereeing;

He maintained strong social networks – family, colleagues, fellow referees, neighbours – and still has a busier social life than many people a fraction of his age;

He lives with a deep sense of gratitude, purpose and care for others, waking each day thankful for “another day”.

None of these guarantee a life without dementia – and Brian is the first to say that much about our brains remains mysterious. But together, they form a pattern we now recognise across many super-agers: a life rich in connection, movement, meaning and kindness.

We also know that up to around half of dementia cases are influenced by modifiable factors across the life course – things like education, blood pressure, diet quality, physical activity, social isolation, depression and air pollution. Many are outside an individual’s control, which is why systemic change and research investment matter. But stories like Brian’s remind us that how we live, and how we support each other to live, matters deeply.

“Enjoy what you’ve got.”

Asked for one piece of advice for younger generations about living a long, meaningful and mentally vibrant life, Brian doesn’t overcomplicate it:

“Enjoy that life. Look forward to that life. Every day is a different day but enjoy what you’ve got.”

He is equally clear about what he hopes his legacy will be, especially for his family: “For them to realise that I’ve loved them all the time they’ve been with me. What I leave them, I give with love. I adore my family. I really do.”

Behind the humour and the Australian bluntness lies something very simple: a man who has spent 102 years showing up for other people – as a husband, father, grandfather, worker, referee, neighbour and friend.

He doesn’t see himself as extraordinary. But in a world that can feel “selfish and cruel”, as he describes it, Brian’s steady kindness, resilience and curiosity make him exactly what CHeBA would call a super-ager.

A birthday wish – and a shared responsibility

On his 102nd birthday, Brian will likely do what he always does: enjoy the people around him, tell a few stories, and quietly marvel that he’s here “another day.”

At CHeBA, we celebrate not just his years, but his message:

Ageing is inevitable. Dementia is not

Science and community both matter

Empathy, movement, connection and gratitude are not just “nice to have” – they are powerful threads in the fabric of healthy brain ageing

And above all: we must keep trying.

Happy 102nd birthday, Brian. Thank you for reminding us what a long, meaningful, mentally vibrant life can look like – and for inspiring our ongoing work to ensure that more people can share in it.

If Brian and Rose’s story has moved you, we invite you to turn compassion into action. Your donation helps fund the research that brings us closer to a future where fewer families have to say goodbye, one memory at a time.

Support brain health. Support families. Support the future. CLICK HERE FOR more