Your cities and towns should be designed for the ageing

To use the Starts at 60 tagline, you can’t help getting older.

In fact, the recent United Nations World Population Prospects report has revealed the global population of older people is growing at an unprecedented rate. At the end of 2015 it says 12 per cent of the world’s population was aged 60 or older.

Globally, the population aged 60 or over is the fastest growing. What really stands out in the report is that for the first time in human history there will be more people aged 60-plus than children under 15 by 2050.

This presents a tremendous challenge for those tasked with the responsibility of designing our cities, as an ageing population also means an evolution of housing, transport and social needs are required.

United States architectural designer, writer and researcher, Eric Baldwin says, “Architects and planners must begin moving beyond end-of-life care and nursing facilities to consider the new design challenges posed by older adults who desire active, interconnected lifestyles.”

As a community in its 60s and beyond, you are looking to maintain your independence and freedoms without disassociating yourselves from society. It’s therefore important that developments adjust to maintain that quality of life.

Starts at 60 has previously discussed ways in which you can age at home if you want to, making simple adjustments to your house to accommodate your needs.

Similarly, small adjustments can be that make a huge difference to the accessibility of a city.

Take public transport for example. If you are less likely to drive as you get older, you’re going to want public transport to be readily available and within walking distance.

“The average person over the age of 65 averages a walking speed of 3km/h,” says Stefano Racalcati of global engineering firm Arup. “At 80 that goes down to 2km/h… Reducing the distance between transport stops, shops, benches, trees for shade, public toilets and improving pavements and allowing more time to cross the road all encourage older people to go out.”

An example of a space where the over-60s can feel comfortable is in Spain. Eric Baldwin says, “The construction materials and finishes used are therefore familiar, warm and comfortable, such as ceramic and wood, to create a homely, relaxed atmosphere.”

Cities could also look at including into their designs wider pavements to encourage more active lifestyles, fewer trip hazards and the location of LCD signs might also make it easier for people with Alzheimer’s disease and dementia to navigate the streets. Such action is already being undertaken in Berlin and Milan.

In places like China, where demographic changes are having a serious impact on the family structure — fewer opportunities exist for the older generation to be taken care of by their extended family, as is traditional — the increased design and development of retirement communities is taking shape.

As more cities experience a demographic shift, age-friendly architectural design is a necessary consideration. The future of housing and mobility is not only being shaped for the over-60s, it’s sometimes being done by them.

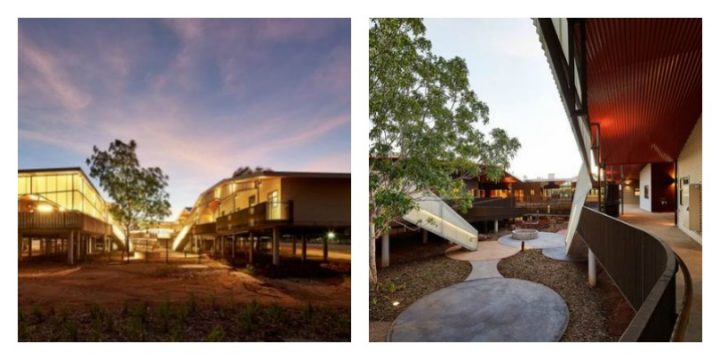

In Australia, the Walumba Elders Centre, built to serve the remote Aboriginal community of Warrmarn, has become a focal point for bringing people together. It provides both self-care and high-level care to its residents. A design element of particular interest is the rising of the project above natural ground level as a conceptual bridge between generations.

An ageing population forces all of us to think about how it can all work, especially with increasing costs of living, reduced pension rates and the need and want of people over the age of 60 to keep working.

Proudly Australian owned and operated

Proudly Australian owned and operated