One of Australia’s most chilling unsolved mysteries

This post continues the strange mystery of the Horseshoe Bridge sabotage. Click here to read part one.

The following morning, Sub-Inspector Marshall of the Brighton police found a soft brown felt hat with red lining beneath the bridge. Seeing this as a potential clue, he made inquiries and found that a storekeeper in nearby Pontville, Joseph Hinds, had recently sold two.

One of these was still in the possession of its owner. The other was traced to a former railway employee, Charles Briggs, aged 27, who lived near Pontville. As he claimed to have lost his hat the previous evening, his movements came under close scrutiny.

On the morning of September 20, Briggs was alleged to have been wearing his hat at the Bridgewater saleyards, where he purchased a cow, but which he later lost.

Briggs had spent some time in the Derwent Hotel, in Bridgewater, before leaving, partially intoxicated, at 6 p.m. with William Jackson, a local blacksmith. The men walked along the main road towards Brighton until they arrived at a rural property known as Parkholme, where Briggs suddenly left Jackson, climbed a roadside fence, and ran across a paddock towards the railway.

At 7 o’clock that evening, Douglas James and Alfred Wood were working in a stable on Wood’s farm, known as the Lawn Retreat, which was some 300 yards from the Horseshoe bridge. Both men heard clanging hammer blows from the direction of the bridge, and assumed some gangers were working late.

At ten minutes to eight, Briggs walked into the Enterprise Hotel, which stood opposite the Brighton Junction railway station. He loudly remarked that he had lost his hat, and stayed in the bar for some time.

The next day, with news and rumours raging in the small community, Briggs was noticeably reluctant to join any discussion of the matter. He preferred to concentrate on finding his missing cow.

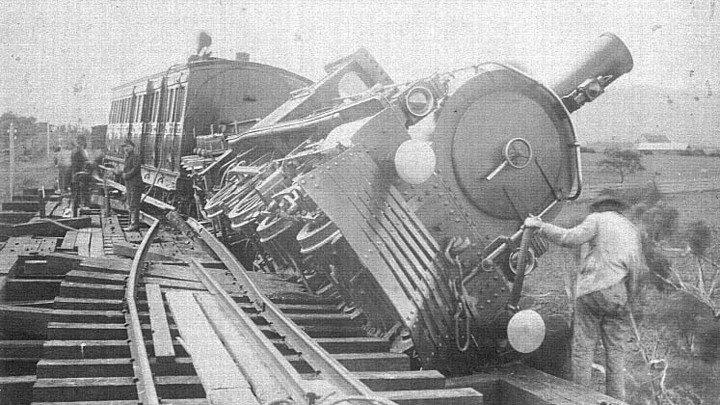

The General Manager of the Tasmanian Railways, Frederick Back, had taken immediate steps to start the complex and difficult task of re-railing the train and restoring the track, assigning several teams of gangers to the awkward task.

But tragedy struck shortly after 5 p.m., when two gangers’ trolleys collided near Bridgewater. Most of the workmen fell off and received minor injuries; but one was badly injured and died as he was being taken by train to the nearest hospital, in Hobart.

On Saturday, September 23, Superintendent Hedberg and Sub-Inspector Marshall interviewed Charles Briggs at his home. As his replies to their questions did not tally with what other witnesses said, he was arrested and taken to the Pontville watch house.

The Pontville court room was crowded when Briggs was formally charged the following Monday, remanded in custody and escorted back to the watch house.

The crowding at this small Court building was repeated when the inquiry into the derailment commenced on Monday, September 30. The evidence of 22 witnesses was heard. Briggs was again remanded in custody and committed for trial at the next Hobart Criminal Court sittings.

On Tuesday, December 12, 1893, Charles Briggs appeared before the Chief Justice and a jury. He pleaded not guilty to two counts, that on the evening of September 20th last, he unlawfully moved the rails and sleepers of, and placed obstacles on the main line of railway with intent to commit murder.

The second count charged him with committing the same offence with intent to endanger the safety of passengers travelling on the line.

Although 23 witnesses appeared for the Prosecution, doubts were successfully cast by Defence Counsel as to whether the hat found beneath the bridge actually belonged to Briggs.

Was it lost by another person elsewhere? Did the strong wind blowing at the time happen to send it into the gully beneath the bridge?

Briggs had claimed that he had lost his hat near the adjacent Jordan River. If so, it was never found.

But, several passengers had seen three men, lurking near the bridge immediately after the derailment. They had disappeared without saying a word. Who were they?

Could a man under the influence of alcohol, as Briggs was, walk across the railway bridge without falling between the sleepers, singlehandedly move heavy rails and place the other obstructions, then walk to the Enterprise Hotel in Brighton, in 1 hour 45 minutes?

At 12.45 p.m. the jury retired to consider their verdict, which had to be unanimous in view of the capital charge involved. By 10.15 p.m. the jury foreman advised there was not the slightest possibility of such a verdict.

The jury was discharged, and Briggs was remanded again till the next sittings of the Supreme Court.

He languished in the Hobart Gaol over Christmas 1893, and it was Tuesday, February 27, 1894 when the second trial commenced. (This trial continued for two days, hearing evidence from the same witnesses.)

At 6.40 p.m. on Wednesday, February 28, the jury retired. Again, the Court was advised that there was no possibility of a unanimous verdict, with 10 jurymen rigidly in favour of an acquittal and 2 in favour of a conviction.

Charles Briggs was released from custody on Friday, March 2, 1894, to face an uncertain future, in view of the stigma now attached to his name and the high unemployment of the time.

So, the questions remain unresolved to this day: did Briggs cause the Horseshoe bridge derailment, and attempt to murder 60 people aboard the train in cold blood? If so, why?

Or, was he an innocent victim of circumstances, which resulted in months of unjust imprisonment? Did the real culprit go free? What of the sinister sighting of the three men near the bridge by some of the passengers?

No one will ever know the truth.

What could have convinced somebody to derail a train? Do you have any theories about this unsolved mystery?

Proudly Australian owned and operated

Proudly Australian owned and operated