Eric Clapton’s tell all account of his devastating realisation

Clapton’s biography accounts how he realised the people around him weren’t who they said they were – his sister was his mother and his parents were his grandparents.

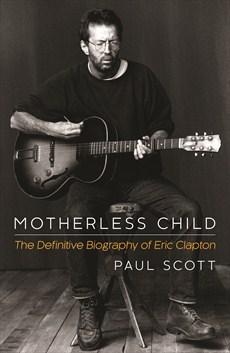

Please enjoy this extract from Motherless Child that sheds light on the life of influential musician, Eric Clapton.

Chapter Two — Pat

One image stands out, pin-sharp and Technicolor, amid the muddy monochrome of the dingy post-war years. It is of a woman, hard and beautiful, emerging as if spot lit by a Hollywood cinematographer from a throng of passengers disembarking down the gangplank of an ocean liner at Southampton in 1954. Among the milling and mayhem, the sea of blurred faces and the bric-a-brac of snatched conversations and shouted welcomes, she holds the eye, serene and aloof, her auburn hair swept up fashionably high on her head, one small child clutching her hand, another in her arms. It is a picture of cold glamour, of latent power and unattainable longing.

Clapton was nine the first time he remembers setting eyes on his mother Pat. She had spent the previous seven years in Canada, where she was married to a Canadian called Frank McDonald. They had made a family of their own in the intervening years, Eric’s half-brother Brian, who was six, and a half-sister Cheryl, one. Now Pat and the children were arriving out of the blue, and Eric and his grandmother Rose were waiting to meet them at the dockside.

He had been told by Rose and her husband Jack that he was meeting his sister. But despite his tender years, Eric was already wise to the deception. From as far back as he could remember, he was used to picking up fragments of conversations when relatives met for gossipy get-togethers at the family home at 1 The Green, Ripley, Surrey, or on Sundays, when he was taken for a weekly bath at the nearby flat of his Auntie Audrey, his grandfather’s sister. He would sit on the floor, as if invisible, as some aunt or other would ask Rose, ‘Have you heard from his mother?’ The rationale seems to have been that the young Rick, as he was known to everyone, would find out soon enough. After all, the fact that Pat, who was Rose’s youngest child, had got herself ‘in trouble’ by a Canadian soldier during the dog days of the war was pretty much an open secret, traded with increasing carelessness behind the lace curtains by Ripley’s closely knit, insular housewives who practised a narrow-mindedness neither more nor less typical of the times. At home, his big brother Adrian, who was actually his uncle, used to call him ‘Little Bastard’. Rick may have had a New World bloodline, but Old World prejudices die hard.

His illegitimacy made him stand out, but he was not alone. Some 30,000 children were estimated to have been born to unmarried British women and Canadian servicemen during and immediately after the war. Between 1939 and 1945, nearly half a million Canadian soldiers poured into Britain, with most stationed in southern England. Upwards of 330,000 passed through training in Aldershot, twenty minutes away from Ripley, and were given the task of defending

England from invasion, with so many of the country’s own soldiers fighting abroad. And in the cramped south-east, that meant young men, often away from home for the first time, were looking to pass the time by going to dances and meeting local girls.

One of those girls was fifteen-year-old Pat Clapton. She was born the daughter of Rose Mitchell, from Rose’s first marriage to Rex Clapton, an Oxford-educated son of an Indian army officer. By all accounts, his courtship of the working-class Rose had caused ructions with Rex’s well-off parents, who did their best to persuade their son against marrying her. Even so, they did get married in 1927, but not – scandalously for the time – until several weeks after the birth of their first child, Adrian. Two years later came a second child, Patricia. But in 1932 Rex died of TB, and Rose and the children returned from Woking to the village of Ripley, five miles away, where she met her second husband Jack Clapp. They married in 1942.

When the teenage Pat’s son, christened Eric Patrick, was born on 30 March 1945, he was officially given his mother’s surname of Clapton. But in reality, the deception had begun before Pat went into labour. Her baby would be born secretly in the upstairs bedroom of Rose and Jack’s tiny house. Eric’s newborn cries were for a mother who would, because of Dickensian convention, be forced to disown him the moment he took his first breath. The plan was simple and age old: Pat, little more than a schoolgirl herself, would cast herself in the role of the new baby’s elder sister and her mother Rose, Eric’s grandmother, would assume the part of his natural mother. From now on, the baby would be known to everyone locally as little Eric Clapp, Rose and Jack’s boy.

Nor would the charade be complicated by the need to explain away the presence of the baby’s father. He was long gone. He had been a married Canadian airman called Edward Fryer, whom Pat met at a dance, where he was playing piano in the band. Eric would not even learn the name of his natural father for another fifty-three years. Even then, his mother was non-committal about whether Fryer was actually his father. There may have been other boyfriends, he wondered. Either way, Clapton never felt able to pin Pat down on anything but the bare facts of his birth and she would, eventually, take the secrets of the past to her grave.

But charade it was. Even from the outset, the conspiracy was only partially successful. Indeed, the fact that Pat had been ‘going with’ a foreign serviceman was pretty widely known in Ripley. Now the village is part of the commuter belt; at the end of the war, and for some time after, it was a country community of poorly paid agricultural workers whose lifestyle had not changed greatly in a century. With not much else to do, people liked to gossip, and the topic of much of that gossip was Pat. She was subjected to a vicious campaign of hatred by the locals. Kids spat at her in the street, malicious graffiti appeared on walls around the village. Pat, a feisty figure not prone to letting bygones be bygones, understandably bore a grudge about her treatment until the end of her life. She once said: ‘It was a hard time, but I’ve got a long memory for the people who black-listed me then. There’s people in Ripley who wouldn’t walk on the same side of the street as me in those days. Now, because of Eric, they cross the road wanting to talk to me.’

Pat stayed on only until Eric was two, and left for Canada after meeting and falling in love with Frank McDonald who, like Fryer, had been stationed nearby. Now she was back, striding off the ship after her transatlantic voyage, ready to torpedo Eric’s apparently idyllic world.

She arrived bearing gifts: brightly coloured silk jackets with dragons on, pretty lacquered boxes that Frank had sent over from Korea during the war. Eric remembers his mother as good-looking, but with a ‘coldness to her looks, a sharpness’. For the next twelve months, she, Brian and Cheryl moved back into the family home in Ripley and the whole can of worms was re-opened. Little, if any, thought appears to have been given to how this would affect the nine-year-old Eric. But at some point in the weeks after she arrived, it became clear to him that the woman he was supposed to think was his long-lost big sister was in fact his natural mother, back home, apparently for good. For a time, the unspoken truth remained firmly off the agenda, though

Eric’s grandparents, Rose and Jack, were certainly aware that he knew

Pat was his real mother.

Finally, imagining that the pretence was all but dropped, Eric blurted out one evening to Pat: ‘Can I call you Mummy now?’ There followed a moment of excruciating and embarrassed silence. Finally, Pat spoke, her voice soft and kindly. But her rejection of him had already passed between them in the preceding long moments of cruel quietness. ‘I think it’s best,’ she began at last, ‘after all they’ve done for you, that you go on calling your grandparents Mum and Dad.’

‘I had expected she would sweep me up into her arms and take me to wherever she had come from,’ Clapton would recall later.

On such moments do lives turn. It was as though a switch had been flicked. Almost immediately, feelings of resentment and rejection turned to visceral hatred and bitterness. The once well-adjusted schoolboy, who had passed his early life in trouble-free good humour, became overnight a surly, withdrawn and sour-tempered spectre in the house. All attempts at affection were rebuffed. Brian, his younger half-brother, who instantly looked up to Eric on his arrival, was given the cold shoulder, particularly because he and his younger sister were given star treatment by the kids in the village, thanks to their North American accents.

Eric got his attention fix by throwing high-decibel tantrums. One day, in a temper, he stormed out of the house and made his way to the green, the piece of communal grass in front of the house. Pat, seeking to placate him, followed him out. ‘I wish you’d never come! I wish you’d go away!’ he shouted at her.

The upsetting incident only served, in his mind, to underline just how charmed his rural existence had been up until his mother’s unwelcome return from foreign shores. Until then, his world had revolved around Rose, Jack and his uncle, Adrian. Rose, gentle natured, kind and indulgent, had a deep scar under her cheek from when, aged thirty, she was in the middle of having an operation performed on her palate and a power cut meant the surgery had to be abandoned. It left her with what looked like a deep depression on the left-hand side of her face. To make extra money for the family, she would sometimes go out to clean the bigger houses on the edge of the village. Jack, well-built and ruggedly handsome, with the centre-parting of a pre-war footballer, smoked roll-ups and, for the most, lived according to the accepted version of maleness passed down through the Clapp/Mitchell clan. A benevolent authoritarian, he avoided any show of affection like the plague, on the assumption, apparently, that human warmth in a man denotes inherent weakness of character.

However, he attended to his working life with care and devotion and Jack was a master plasterer, master carpenter and master bricklayer. Rose and Jack’s home, like the rest of the houses in the same row, had formerly been an almshouse. It consisted of four simple rooms, two bedrooms upstairs and a small front room and kitchen down stairs. It wasn’t exactly a case of all mod cons. There was no bathroom, just an outside loo, no electricity and gas lamps to light it. Rose and Jack had one bedroom and Uncle Adrian the other. The young Eric slept on a camp bed, either in his grandparents’ room or, later, downstairs.

The summer months were spent outside, on the green on to which the front door of the house opened. The fields that surrounded Ripley became his playground, as did the banks of the River Wey and the ‘Fuzzies’, as the woods beyond the green were known to the local kids. Throughout, the young Eric’s capacity for mischief went no further than stealing sweets from the village sweetshop, owned by the Farr sisters, where rationing was still the order of the day.

The change in his character due to the painful episode after his mother’s arrival was marked. Where once he had been an attentive and interested pupil at Ripley Church of England Primary School, now he became insolent, resistant to authority and self-contained. Not surprisingly, his work suffered. The safety he felt as part of a family evaporated. He imagined people were talking about him, whispering behind hands. ‘I wanted the ground to open up and swallow me,’ he remembered. ‘I thought I was obviously a piece of shit and that was why I had been treated in the way I had been.’

It also coincided with him developing the first of many addictions – in this case a serious dependence on sugar, which he ate in bread and butter sandwiches. Nor was the rejection by his mother the only thing he was struggling with. By chance, at around the same time he discovered his illegitimacy, he caught himself in profile in the mirror and noticed, to his horror, that he had a weak chin. ‘I was playing around with my grandma’s compact, with a little mirror you know, and I saw myself in two mirrors for the first time . . . I was so upset. I saw a receding chin and I thought my life is over,’ he said later. As soon as he was old enough, he would begin the process of camouflaging this apparently grave anatomical defect with beards of various lengths, something which lasted for most of his adult life.

To make up for these early disappointments, he retreated into a world of make-believe, occupied by larger-than-life characters. Principal to this parallel existence was the young Clapton’s alter ego, the dashing Johnny Malingo, a suave man/boy who meted out brutal force to anyone daring to get in his way. Crucially, his creation, Malingo, sought no friendships other than the family’s black Labrador, Prince. Instead, he demanded respect through sheer force of will. Johnny would sometimes become a cowboy and ride on another of his creations in this fantasyland, Bushbranch, the pony who went with him everywhere.

Eric would also sit downstairs in the kitchen drawing obsessively. Bizarrely, an early fascination was for sketching pies. Perhaps because he was the baby of the family, perhaps because his grandparents felt guilty about his predicament, he was spoilt by them. Rose would go out and buy him the latest comics, from which he would copy the characters, and Jack spent his free time making him toys to play with. Later, Rose kitted him out with a bamboo fishing rod, reel and tackle, bought ‘on tick’ in weekly instalments from a catalogue.

Such indulgence didn’t stop him getting into trouble. Not long after Pat’s arrival, the nine-year-old Eric was playing out on the green when he discovered a rather rudimentary homemade version of Penthouse magazine, featuring various pages stapled together on which were hand-drawn pictures of genitalia. Fascinated and shocked by the crudely sketched images, it gave him the courage to ask the new girl in his class: ‘Do you fancy a shag?’ Of course, all hell broke loose and he found himself paraded before the ginger-haired Scots headmaster, Mr Dickson, who insisted an apology was forthcoming to the girl and administered ‘six of the best’ for his troubles. For a naïve schoolboy, unsure of what exactly he had asked his classmate to do in the first place, it must have been a deeply affecting experience. From then on sex might well have become associated with shame and punishment, a source of sullied fascination, but fraught with the risk of humiliation and retribution. That bitter legacy would be the cause of much more angst to come. Moreover, his fractured relationship with his mother would only serve to crystallise further his sense of anger towards all women. ‘She abandoned me and I blamed her,’ he has said of her rejection of him. ‘That is where it all began. Then I realised I was capable of doing exactly the same to the opposite sex – and worse than she ever did to me.’

Having wreaked havoc with her homecoming, less than a year after showing up, Pat suddenly disappeared back to Canada with Eric’s half-siblings, leaving him to deal with yet another abandonment. Because of his lack of effort in the classroom, it was no surprise to Rose and Jack when Eric failed his eleven-plus examination, which would have ensured him a place at Guildford or Woking grammar schools. Instead, he was dispatched to St Bede’s Secondary Modern in nearby Send. If failing to get into grammar school was a disappointment, it was more than made up for by the fact that virtually all his friends from the village were also making their way to St Bede’s, in likely preparation for eventually being taken on as apprentice tradesmen or by the nearby Stansfield fizzy-drink factory, where Eric got a mind-numbingly dull holiday job sticking labels on bottles of lemonade.

While he may have been happy to be at school with all the familiar faces from Ripley, the sense that he was – and would remain – an outsider was already imprinting itself. He had no interest in football or cricket, unlike the rest of the boys in his year – though he would develop belated fascinations with both sports. Instead, he acquired parallel nascent obsessions, with clothes and buying records. These passions he shared with his only real friend, John Constantine.

John’s well-off parents had a radiogram – part wireless, part record player – which was out of the reach of most families in the village, Clapton’s included. Together, John and Eric would listen to 78s of Elvis Presley’s ‘Hound Dog’. John’s family also had a TV, a rarity in 1956 Britain, which gave the awestruck Clapton his first glimpse of a Fender Stratocaster guitar, which looked like a cross between an American car and a rocket ship, as played by Buddy Holly on Sunday Night at the London Palladium. Constantine was the embodiment of the lifestyle to which Clapton aspired, where money and possessions bought the respect and status he craved. But there was something else too, an assuredness and certainty the Constantine family had about their position that seemed to come naturally to the higher social orders and which the adolescent Eric found magnetic. It would become a feature of numerous of his significant relationships in the years to come; he was drawn to those possessing not just money and status, but the unwavering certitude of where they fitted in to things. That assuredness didn’t reach as far as their schoolmates – to them, Eric and John did not fit in at all. He and the ‘posh’ Constantine were dismissed sneeringly as ‘the Loonies’ and subjected to the sort of low-level abuse that leaves scars nonetheless.

In 1957 Rose bought Eric his own record player, a Dansette, on which he played Buddy Holly and the Crickets, Elvis and Little Richard. They became his crutches and they helped him forget. Music became a refuge for the young Clapton.

And music was in his blood. Rose’s father, Granddad Mitchell, played the accordion and violin and, as a girl, Rose had learnt to play the piano. She kept a harmonium in the front room in Ripley, later replaced by a small upright piano, at which she would croon popular Gracie Fields and Josef Locke tunes of the 40s. And Eric’s Uncle Adrian could play the mouth organ and fancied himself as a dancer. When Adrian wasn’t Brylcreeming his hair or tarting up a succession of Ford Cortinas with fake-fur interiors, he was listening to his beloved jazz – Benny Goodman and the likes of the Dorsey Brothers. Eric was bought an old violin by his grandparents and for a while tried to emulate what he heard his Granddad Mitchell playing on the instrument, but he quickly gave up, put off by the discordant screeching of bow on strings whenever he picked it up. There would be a few more false starts to come before he could begin making music himself.

Available for $29.75 via Booktopia

Do you enjoy reading biographies? What did you think of this extract? Tell us below.

Proudly Australian owned and operated

Proudly Australian owned and operated